June 2nd, 2023

Éric Schnakenbourg

Often overlooked in the broader history of the trade of enslaved African peoples, the princes of the countries bordering the Baltic Sea also sought to engage in this activity. Due to their own limited resources, they were forced to look overseas to mobilize the skills and capital needed to support enterprises which were often far from successful.

The history of the trade of enslaved African peoples was dominated by the great imperial powers, but other smaller states also deported populations from Africa. Several princes on the shores of the Baltic sought, with varying fortunes, to take advantage of the financial windfall represented by transatlantic trade. These included the Kings of Denmark and Sweden, the Duke of Courland (territory corresponding to current-day Latvia), and the Prince Elector of Brandenburg. Whereas in England, France, and Portugal, the trade in enslaved peoples was integrated into an imperial structure, and in the 18th century, into the plantation economy, trafficking in Baltic Europe was based on a different model in many respects. The Scandinavians participated only marginally in the great Atlantic trade of enslaved African peoples. They are believed to have been responsible for about 1% of all deportations of Africans to America between the mid-17th century and the early 19th century. Nonetheless, the study of powers lacking a real empire in America raises questions about the relationship between the trade of enslaved peoples and colonization.

From the beginning of the 17th century, the circulation of information on a European scale and the fluidity of the marine and merchant domains fuelled the interest of the princes of Baltic Europe in African trade and, more broadly, in Atlantic trade. As early as 1625, a Danish company based in Glückstadt, in northern Germany, operated its first campaigns to America, but the initiative remained episodic. Africa began to be regularly frequented by the Danes following the establishment of three forts on the Gold Coast (current-day Ghana) between 1649 and 1666. Shortly afterwards, in 1672, they occupied a first island in the French West Indies, Saint-Thomas, before expanding to neighbouring Saint-Jean in the years that followed, and then buying Sainte-Croix from France in 1733. Other Nordic princes also wanted to engage in trafficking during this period. The Swedes began to take an interest in it in 1649, when a Swedish African Company was established in the town of Stade (northern Germany). The Company bought a territory on the Gold Coast and built a first fort there. It was from here that African captives were deported first to São Tomé, and then to Curaçao, before it was conquered by the Dutch in 1658. During their brief presence in Africa, the Swedes are said to have deported between 1,500 and 2,000 individuals.

One of the lesser-known attempts is that of Jacob, Duke of Courland. He was behind the founding of small forts in The Gambia in the early 1650s, as well as a settlement in Tobago. While there is no formal proof that the Courlanders engaged in the transatlantic trade of enslaved African peoples, they were undoubtedly involved in intra-African trade. Their adventure was cut short in the 1660s when they lost their Atlantic establishments. In the late 17th century, Brandenburg in turn embarked in the trade of captives with the sending of two ships to Africa in 1679. This first attempt encouraged the Prince Elector Frederick William to found the Brandenburg African Company. The latter was at the origin of a first establishment named Gross-Friedrichsburg on the Gold Coast in 1683. Unable to set up a colony in the French West Indies, in 1685, the Brandenburgers rented part of the Danish island of Saint-Thomas. From this point onwards, they engaged in the trade of enslaved African peoples, reselling them to the neighbouring colonies. However, the European wars at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries contributed to the downfall of the Brandenburg African Company, which sold its forts in 1716. By that time, it had organized over fifty-five trafficking campaigns and deported 20,000 to 25,000 Africans to America.

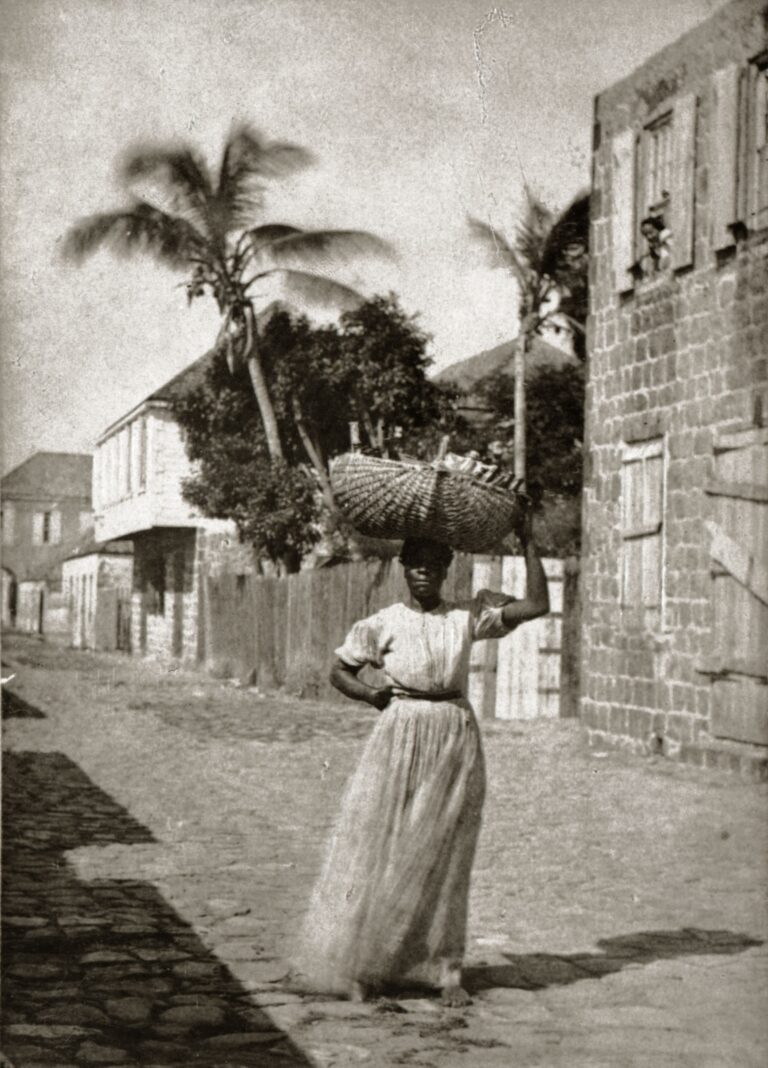

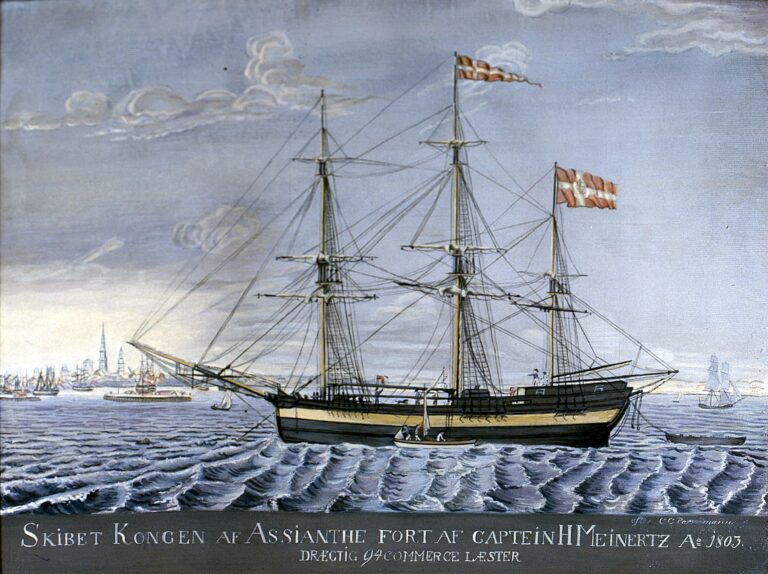

The Danes had a lasting presence in Africa and the French West Indies from the late 17th century onwards. They carried out three-hundred-and-forty-nine trafficking campaigns between their Atlantic settlements between 1647 and 1806 and deported over 100,000 Africans. Trade was irregular however, as at the beginning of the 18th century, there were frequently periods lasting one or two years without any expeditions at all. The boom years of Danish trade in enslaved African peoples were between 1795 and 1805, particularly in 1802 with 5,223 deported slaves. Danish trafficking stemmed from a dual motivation. The first was to provide labour to Sainte-Croix, the only one of Denmark’s colonies that had developed sugar-cane plantations. As in the other territories that had adopted the plantation economy, enslaved workers made up about 90% of the population. The second motivation behind Danish trade concerned more the islands of Saint-Thomas and Saint-Jean. In the absence of significant plantations, these served as a transit centre for deported African captives who were then sold onto other European colonies. It is estimated that in the 18th century about 40% of the African captives deported by the Danes were destined for foreign colonies. This number was even greater during the period of the Revolutionary and Imperial Wars (1793-1815), which essentially opposed France and Great Britain. The disruption of traditional supply circuits led to a steep increase in prices. Therefore, the Danes became a major supplier of enslaved labour to Cuba in the 1790s.

Danish trade inspired the Swedes who subsequently increased their efforts to obtain territory in America. In 1784, France ceded the small island of Saint-Barthélémy to the Swedes, who made it a place of transit for the re-deportation of captives arriving from Africa to other European colonies. Between 1785 and 1839, it is estimated that two thousand enslaved persons landed in Saint-Barthélémy. However, most of the trading done under the Swedish flag did not pass through this island because the ships went directly to those locations where they could sell the captives for the best price, notably the Spanish or French colonies. This activity more than likely concerned over 7,500 Africans. The trading of captives from the Swedish island was particularly prosperous in the first decades of the 19th century. Saint-Barthélémy, open to all traffic, was an attractive market in enslaved individuals that drew traders and colonists of all nationalities.

Unlike the great powers of the Atlantic world, firmly established on the African and American coasts on either side of the Atlantic, one of the difficulties facing the Nordic princes was the ability to possess the facilities needed in the embarking and disembarking of captives. In any case, they adopted strategies to acquire one, then the other. They began in Africa, because trading forts were less expensive to maintain than a colony, which could not be developed without enslaved labour. It was at this time that the Nordic powers invested in intra-African trade between the continent and São Tomé or the Canary Islands. The possession of an American establishment allowed them, after a few years of experience, to participate in transatlantic trading proper. It is telling that the Danish and Brandenburg African Companies added “America” to their name to clearly indicate their presence on both sides of the Atlantic.

Undoubtedly, the primary specificity of Nordic participation in the transatlantic trade of enslaved African peoples was the cosmopolitan dimension of their enterprises. The Dutch played a fundamental role in launching various Nordic trading expeditions in the 17th century. They had the experience and were already integrated in networks that allowed them to raise funds but lacked the legitimacy of a State to launch new operations. In Brandenburg, the Dutchman Benjamin Raule, who held the position of “Director General of the Navy” was the kingpin of the trading company. He managed to raise capital from local investors, the Prince Elector and his entourage, but also from Rotterdam merchants. This was indeed a German-Dutch company whose headquarters were in Emden on the border between the United Provinces and Brandenburg territories. In the major trading centres of northern Germany, like Lübeck or Hamburg, some investors also placed funds in Scandinavian companies. In Africa, the establishments of the Nordic princes were frequented by English, Dutch, and French smugglers who compensated for the insufficient supplies coming from the metropolises. The strong presence of foreign investors explains why part of the profits from trading escaped the country spearheading the campaign with its flag.

Finally, Baltic Europe was also indirectly involved in the great Atlantic trade of enslaved African peoples. On the one hand, in the late 18th century, Scandinavian investors placed their funds in foreign trading expeditions. On the other hand, goods from the North were used to buy captives in Africa. This was the case, in particular, for the weapons of Danish manufactures and, above all, for Swedish metallurgical products, like copper or brass. However, the most sought-after Nordic product was bar iron. It was generally exported from Sweden or Russia to the ports within the major trading countries, before being sent back to Africa to be exchanged there for captives. Depending on the location, it often represented 12 to 20% of transactions.

Finally, if the Nordic countries were minor players in overall European trafficking, they were nevertheless involved in this type of trade, both directly and indirectly. Although small in volume, their participation may have played a significant role at certain periods, thereby contributing to the sustainability of the plantation system based on enslaved labour, for example. The limits of the means at their disposal to participate in Atlantic trade forced them to open their businesses to foreigners, mainly the Dutch and Germans. Far from being anecdotal, trade seen from a Nordic perspective shows just how open and fluid European capitalism and the enslavement system was. Only the Danes managed to sustainably practice Atlantic trade due to their continuous presence in both Africa and the French West Indies, and their ability to resist the major powers, while being useful to them during periods of conflict. That said, Denmark was the first European country to enter into the process of banning this type of trade in 1792, under the influence of English abolitionists.

About the author

Eric Schnakenbourg is professor of modern history at Nantes Université and director of the Centre de Recherches en Histoire Internationale et Atlantique (CRHIA). His work focuses on the history of international relations in Europe and the Atlantic world in the 17th and 18th centuries. He is the author of Le Monde Atlantique: un espace en mouvement XVe-XVIIIe siècle (Armand Colin, 2021), and Entre la guerre et la paix: Neutralité et relations internationales, XVII-XVIIIe siècle (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2013).

Bibliography

Emmer Pieter, “Slavery and the Slave Trade of the Minor Atlantic Powers” in David Eltis (ed.) et alii, The Cambridge World History of Slavery; vol. 3, AD 1420-AD 1804. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011, p. 450-475.

Gøbel Eric. The Danish slave trade and its abolition. Leyde: Brill, 2016.

Naum Magdalena, Nordin Jonas. Scandinavian colonialism and the rise of modernity. Small time agents in a global arena. New York: Springer, 2013.

Schnakenbourg Éric, Maillefer Jean-Marie. La Scandinavie à l’époque moderne. Fin XVe-début XIXe siècle. Paris: Belin, 2010.

Weiss Holger. Ports of globalisation, places of Creolisation: Nordic possessions in the Atlantic world during the era of the slave trade. Leyde: Brill, 2016.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.