June 7th, 2023

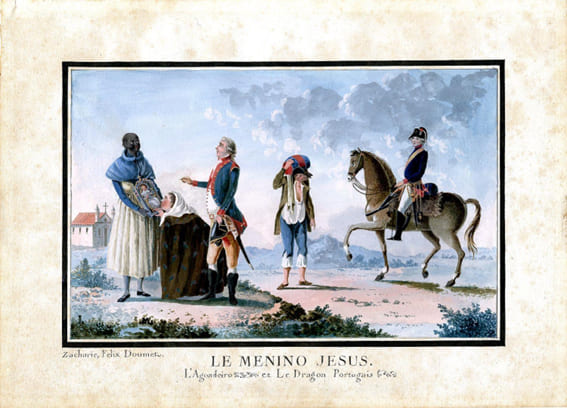

The presence of African slaves was a common trait of the Portuguese society that many travellers highlighted in their accounts of the country. Their number increased over time, although it is not possible yet to have a clear idea about their percentage vis-a-vis the Portuguese population. They were in charge of daily life tasks, as well as of economic activities, helping to increase the income of their owners.

Even before Portugal’s pioneering role in the Atlantic trade of enslaved people, the presence of slaves was embedded in the fabric of the country. Portugal used to resort to slaves, namely Muslims from the Mediterranean area, but the maritime expansion brought a substantial number of captives to the country. Slaves landed in Portugal not only by means of the Atlantic trade of enslaved people but also through private individuals, having lived abroad when returning to the country, transported with them the captives they possessed.

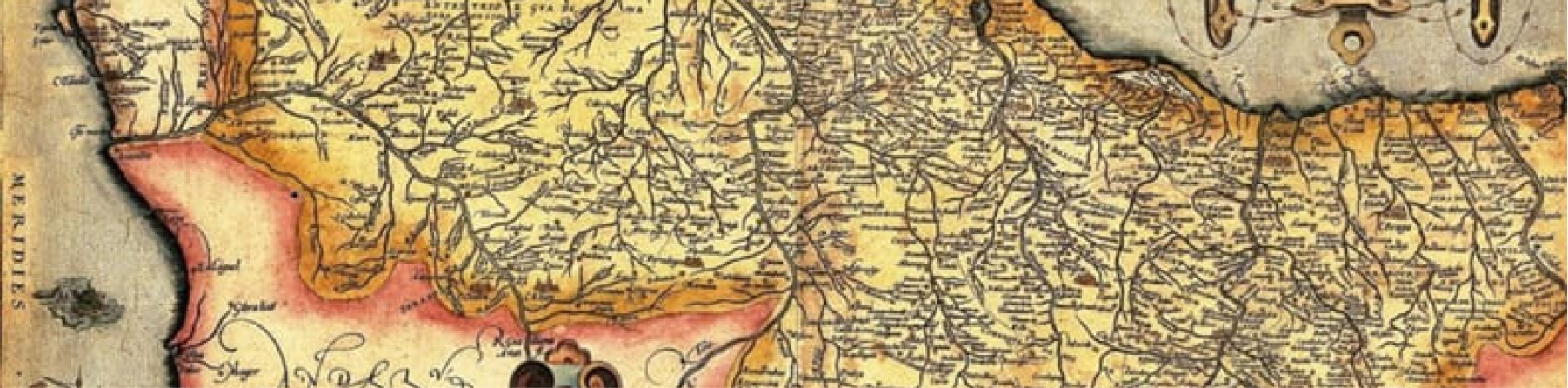

The slaves subjected to commerce in Portugal in the context of the Atlantic trade of enslaved people first arrived in considerable numbers at the Algarvian ports, namely at Lagos in 1444. But, from the 1480s onward and until the 16th century, Lisbon became the main port of entrance of slaves in Portugal. Lisbon was a consumer of slaves, but also a place for the reception and redistribution of captives to other Portuguese cities and abroad, more precisely to Castile and Aragon.

The trade of enslaved people was very profitable in terms of tax for the Portuguese crown, which encouraged the practice. The trade was under the supervision of the overseas administration since in 1486 King D. João II established in Lisbon the Casa dos Escravos (Slave House). Located in the heart of the city, the Casa dos Escravos was responsible for receiving all slave shipments and expediting their assessment, taxation and sale. Afterward, the crown transferred the Casa dos Escravos tasks to the Casa da Guiné e da Mina (House of Guinea and Mina).

Most of the slaves imported to Portugal had their origins in Sub-saharan Africa, coming from Arguim, Cape Verde, Guinea, Sao Tome and Principe, Benin, São Jorge da Mina, Angola and Mozambique. The slave trade in Portugal involved likewise people from Asia, namely from Gujarat, Cannanore, Malabar, Ceylon, Bengal, Pegu, Sion, Java, China and Japan. People from Brazil were also traded in Portugal, but in a limited number.

Different actors took part in the trade of enslaved people to Portugal, including monarchs, public employees, ship owners, ship crews, merchants (Portuguese and foreigners), nobles and members of the clergy. As for the number of slaves shipped to Portugal, the information is not yet fully systematized. In 1519, in line with information gathered from the records of Corpo Cronológico and Núcleo Antigo, the Casa da Mina e Índia received 1496 captives from Arguim. From Cape Verde during the 16th century, based on the Livro de Receita da Renda das Ilhas de Cabo Verde de 1513 a 1516, Portugal received an average of 1000 slaves per year. Between 1525 and 1527, the Corpo Cronológico establishes that Sao Tome and Principe sent 555 slaves to Portugal. According to estimates, Portugal received 2000 to 3000 slaves annually from different places during the 16th century (António de Almeida Mendes, 2004, p.26).

Regarding the volume of the slave trade from Lisbon to other European cities, again it is only possible to gather scattered data. There is some information on how Lisbon supplied slaves by sea and land to other locations on the Iberian peninsula. Not only Portuguese but also foreigners, living in Portugal and abroad, intervened in this trade. In 1510, Alonso Cáceres, a merchant of Castilian origin, shipped 228 captives from Lisbon to Valencia. Two years later, Diego Ferrandiz, a merchant in Lisbon, sent 25 slaves to be sold in the same city. In 1513, Diego de Aranda and Cristóbal de Aro, merchants from Burgos who lived in Lisbon, exported 159 slaves also to Valencia (Vicenta Cortés Alonso, 1964, p. 401, 424, 434-435).

Besides this large-scale trade, slaves were the object of small orders placed by private individuals to ship crews. Likewise, Portuguese living abroad, for instance in Cape Verde and Sao Tome, could send slaves to be sold in Portugal and abroad. Public employees and ship crews had the privilege to transport to Portugal a handful of slaves free of charge, which they later sold.

Descriptions of how the slaves arrived in Portugal reported that they were piled up on the deck of ships, naked, chained and malnourished. After landing, the royal officials or the merchants that had a contract with the crown to exploit the sale of slaves organized their public display. The slaves could be sold in auctions, in groups or isolated. The potential buyers could examine them, touch them and make them move to see their physical condition. Once sold the captives became the private property of merchants, farmers, military, public employees, priests and noble families. Institutions, like convents, monasteries, mercies, confraternities and hospitals, also held captives.

A historical reconstruction of the journey of an African captive is key to illustrate the presence of enslaved people in Portugal. Described in the sources by his Portuguese name, Francisco, a Wolof, became by the middle of the 16th century a captive of the Moorish of Xarife in the course of a war waged against his people. Transported to Arguim, he was then sold by the Moorish of Xarife to the Portuguese captain Jerónimo Sardinha, who carried him to Portugal. At the Casa da Índia, he changed owners, becoming a slave of Bartolomeu Esteves.

The slaves´ presence in Portugal was visible mainly in urban areas and places near the sea, such as Lisbon, Évora, Braga and Setúbal, as well as in the regions of Ribatejo, Alentejo and Algarve. According to some estimations of Cristóvão Rodrigues de Oliveira, an official of the Archbishop of Lisbon, by 1551 Africans represented 10% of the population of the city, counting for 9.950 of its 100.000 inhabitants. In Algarve, in the 8 parishes of the region, the slaves represented 8,4% of the baptized people in the 16th century. In Ribatejo and the villages near Setúbal, also during the 16th century, the amount of slaves baptized was similar, ranging from 6% to 9% of the population. In Alentejo, the number of slaves in relation to the baptized was 5%. In the North of Portugal, the slaves were far less expressive, except for the city of Oporto where the captives represented 6% of the baptized by 1540. Having in mind that not all slaves received baptism, these figures fell short of reality and probably the percentage of captives among the Portuguese population in the 16th century was higher.

The slaves performed different everyday tasks, such as domestic activities, including cooking, cleaning, washing clothes and transporting water. In addition, they were at the service of the economic interests of their owners and according to the regions their activities could require a certain level of expertise. In places near the Tagus river, they were used as boatmen to supply Lisbon with goods. Since agriculture was dominant in the region, in Alentejo the slaves worked on the land and in cattle raising. In the cities, they increased the income of their owners by working as carpenters, bricklayers, blacksmiths, potters, weavers, sellers, dressmakers, fishermen and so on. The owners also rented their slaves for public works, namely to clean and repair streets and pavements.

The slave owners were under the obligation to baptize the captives, although those that were over 10 years could refuse the sacrament. The descendants of the slaves had also to receive baptism and for them there was no room for refusal to comply with the sacrament. The Church allowed marriage among slaves, but sometimes the owners did not facilitate the practice because it could affect their freedom to dispose of the captives. Other owners, on the contrary, were favorable to matrimony since the slave couples could have children and augment their patrimony. It was also not uncommon for the owners to promote slave breeding, to have additional captives to work for them or to sell.

In addition to the deprivation of freedom and the mistreatment they suffered, slaves were subjected to various rules limiting their daily lives. They could only perform certain activities, like for instance manufacturing swords, under the guidance of a professional who was not a captive. In Lisbon, slaves had permission to take water solely from fountain spouts signaled for their use, which were different from those reserved for the white population.

Non-baptized slaves were excluded by the Portuguese authorities from normal forms of burial. In 1515, King D. Manuel I instructed the construction of the Poço dos Negros (Pit of the Blacks) where the bodies of deceased slaves were thrown. Until then, the bodies were thrown in a dunghill in a place named Cruz de Pau (Wooden Cross), used for punishment.

Slaves were furthermore excluded from religious institutions, motivating them to create their own spaces for devotion and social protection, being the Confraria da Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Homens Pretos (Confraternity of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Man) the first of such institutions to be established in Portugal.

Initially captives, in time many slaves became freedmen, living and working in the city of Lisbon. The increase in the population with African origins led to the creation in Lisbon in 1593 of the Bairro do Mocambo (Mocambo Neighborhood), named after an Angolan word meaning small village or place of refuge. Located on the outskirts of Lisbon, the neighborhood signaled the existence not only of captives but also of freemen among the population of the city.

Slaves and freedmen gave a significant contribution to the history of Portugal, in terms of its culture, social life and customs. Some of them rose socially, as was the case of João de Sá, a slave who, after being in the service of a nobleman, worked at King D. João III’s court. Due to his sense of humor, D. João III awarded him freedom and the Hábito da Ordem de Cristo (Habit of the Order of Christ), a high honorific distinction.

By the middle of the 16th century, the number of slaves shipped to Portugal decreased in comparison to those sent to the American continent. Although to a lower degree, the import of slaves to Portugal continued until 1761, when Sebastião José de Carvalho e Mello, then Secretary of State for Interior Affairs of King D. José I, prohibited the entrance of new captives into the country. Afterward, in 1773 he ruled that the children of slaves were free, virtually abolishing slavery in Portugal. But these decisions did not end the existence of captives, which continued to be part of Portuguese society until the 19th century.

About the author

Aurora Almada e Santos is a researcher at the Contemporary History Institute of the New University of Lisbon, a leading institution in the study of the Portuguese contemporary history. Her main research interest is the Portuguese decolonization, namely the international dimension of the struggle for self-determination and independence of the Portuguese African colonies. Her current research activities include the publishing of articles and book chapters, the organization of publications and conferences, as well as the teaching of courses related to African history.

Bibliography

António de Almeida Mendes. “Portugal e o Tráfico de Escravos na Primeira Metade do Século XVI” in Africana Studia, nº 7, 2004, p. 13-30. Can be consulted online: HERE

Jorge Fonseca. “A Historiografia sobre os Escravos em Portugal” in Cultura: Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, vol. 33, 2014, p. 191-218. Can be consulted online: HERE

Jorge Fonseca. Escravos e Senhores na Lisboa Quinhentista. Lisboa: Tese de Doutoramento em Estudos Portugueses, defendida na Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2008, p. 682. Can be consulted online: HERE

Isabel Castro Henriques. Os «Pretos do Sado». História e Memória de uma Comunidade de Origem Africana (Séculos XV-XX). Lisboa: Colibri, 2020, p. 307.

Isabel Castro Henriques. Roteiro Histórico de uma Lisboa Africana. Séculos XV-XXI. Lisboa: Alto Comissariado das Migrações, 2019, p. 108. Can be consulted online: HERE

Isabel Castro Henriques. Os Africanos em Portugal: História e Memória (Séculos XV a XXI). Lisboa: CPPURE, 2011.

Vicenta Cortés Alonso. La Esclavitud en Valência durante el Reinado de los Reyes Católicos (1479-1516). Valencia: Ayuntamiento, 1964.

All rights reserved | Privacy policy | Contact: comms[at]projectmanifest.eu

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry's standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book.